Get formatted versions: Word : PDF

Orientation

Consider a situation where you have three variables: X, Y, and C. Your understanding of how the world works is telling you that X causes Y. And, indeed, when you collect data, you see an association between X and Y. But all an association does is to tell you that X and Y are connected somehow, not what that connection is.

If you’re trying to convince a skeptic that X causes Y, you have some work to do.

The most powerful and compelling way to show whether or not X causes Y is to do an experiment. In an experiment, you set the values for X and observed the corresponding values for Y. For example, in a clinical trial, you would give a drug or placebo to each of the trial subjects and observe the outcome Y.

Let’s see how this works in terms of the possible causal relationships among variables X, Y, and C. Many of these are drawn out in the figure below, with each network labelled (a), (b), (c), and so on.

When you do an experiment by setting X, you change the world. That is, before you did the experiment, X was influenced by whatever variables are causally connected to it, that is, with an arrow leading into X. When you do an experiment, you take over completely (at least, in an ideal experiment). In terms of the diagrams, this means that you erase all arrows leading into X. The outbound arrows, if any, remain.

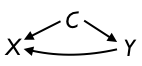

More precisely, since you are determining X, the causal diagram will is transformed from something like this

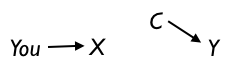

into something like this

into something like this

Activity

For each of the causal networks labelled (a) through (p), examine the network to see which would produce an association between X and Y. (Take the network as is, without erasing any arrows.)

- Circle the networks will lead to an association between X and Y. . . .

a b c d e f g h j k m n o p

The ones you circled are the possibilities consistent with the observation of an association between X and Y.

- Are there any networks among the ones you circled for which Y causes X, either directly or indirectly through C? Underline them . . .

If the answer to question (b) above is “yes,” then your observation of an association between X and Y does not rule out the possibility that Y causes X.

Now let’s see what might happen when you do the experiment. Go through each of the causal networks and erase any arrows leading in to X. Your experiment changes the world (at least for those possible networks that have an arrow leading into X).

- Circle all the networks for which your performing the experiment leads to at least one arrow being erased.

a b c d e f g h j k m n o p

- Among all the networks a through p, when any arrows leading in to X have been erased, are there any networks in which Y directly or indirectly causes X? . . .

Let’s put it more simply …. If you erase all arrows leading into X, is there any possible way that Y or C can cause X? (Hint: There are no causal arrows leading into X!)

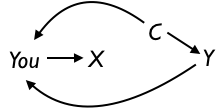

It might happen that in setting X in the experiment, you glance at the values of Y or C and they might influence the way you set X. If this happens, you effectively have not erased all the arrows into X from Y and C. That corresponds to a network diagram like this:

- Think of a way that you can determine what values to set X to that demonstrates compellingly, even to the most skeptical opponent, that C and Y could not have played any role at all in determining X. Explain. . . .

Version 0.3, 2019-05-29, Danny Kaplan, Word version